DancingbyMauveen Wilcox |

Me (aged 10) and my cousin, Doreen Chapman (aged 12) |

In 1942 I was 14 years old and just finished with school. Quite naturally I felt grown up and independent of mind, as I prepared to experience whole new horizons in my, up until then, unexciting daily life. I recollect so vividly that opposite to where we lived, in Tame Street, Bilston, there was a huge hall, belonging to St Mary's Church in Oxford Street. Around that time this hall was converted into a wartime civic restaurant providing cheap subsidised hot meals, mainly for people working in the numerous factories located in and around that area. It operated from Monday to Friday, and on Saturday mornings opened until midday. It was a facility that proved to be extremely popular not only with factory and office workers but also other groups and even school children on a Saturday morning. I can recall that the building was also used for various social functions, such as weddings and private parties and particularly as a refuge and meeting place for handicapped people. I would see them being wheeled along in a variety of wheel chairs and other types of conveyances. I assumed they came together on, a regular basis, for educational or purely social purposes |

Another weekly event that also took place in the hall was a social function that absolutely fascinated me. Most Saturday nights a dance would be held. At 14 years of age I was never allowed to go. In 1942 it was considered totally unacceptable for a girl of that tender age to attend such an adult environment!My grandmother lived in a house next to the bottom of our communal yard and practically every Saturday, as a slight consolation, I would sit on the front step for hour after hour, eagerly watch everyone arriving, the ladies in their long dresses, looking so elegant, and their male escorts in dark suits, complete with shiny black patent shoes. It would never fail to conjure up for me a spectacular, glamorous world of colour and grace that I longed to join as soon as possible.

Then after a while the music would start and I would swiftly sneak into the tennis courts situated next to the hall. Once there it was quite easy to get through a convenient opening which took you to a side area away from public gaze. Then, after collecting a few house bricks which always seemed to be available, I would use them to stand on and obtain a clear view through a side window of the dance floor area. This enabled me to observe couples enjoying all the latest modern dance routines. Eventually I would reluctantly return to my Grandma's house and ask permission to go to her bedroom, which provided a reasonable vision of some of the dancers. Looking back it's fairly obvious where my life long love of ballroom dancing originated.

Practically every local Black Country local authority held a regular programme of municipal dances on fixed nights of the week. These would either be staged at the Town Hall or municipal baths. Without doubt they were looked upon as the top venues for all enthusiasts. If only I had a pound for the number of times in the forties I stood and watched my elder sister Josie getting herself ready to attend a dance taking place at the Town Hall! I would sit on the doorstep of my Grandma's house and gaze at the neighbourhood girls walking while clutching the hems of their long dresses to avoid getting them dirty. Most would have their hair glittering with hair grips. This effect was obtained by attaching shiny stars on the end of the grips. As I think about those early teenage memories, it evokes marvellous nostalgic thoughts of glamour and excitement amid the ever present industrial dirt and grime of those days.

I promised myself that as soon as I was old enough I would join the enormous, ever growing, number of ballroom enthusiasts that existed throughout the length and breadth of the entire Black Country region, many of whom continued to attend dances after they married.

In the thirties, forties and even fifties, it was customary for any girl going to a dance to be accompanied by a regular partner. This presented a thin, pasty individual such as I undoubtedly was, with something of a problem. But I managed to overcome that difficulty by joining a group of similar-age old school friends who also belonged to the same church choir. We decided to attend, as a group, a new monthly dance at our old school, specifically provided for the benefit of ex-pupils.

Most schools in the area held similar dance evenings and they all operated to a set formula. The whole venture would be organized by members of the teaching staff. Everyone crowded into a somewhat confined dancing space, usually created by removing the dividing partitions between two a suitable class rooms. Music was provided by a record player. Amid much laughter and giggling we were requested to choose a dancing partner, and each time the music stopped, for partners to change quickly, as the boys were all being jeered at by their mates. It took a great deal of nerve to be the first volunteer to take that defiant walk across the floor and ask someone to dance. What I do remember of those memorable dance nights is that everyone thought they were great fun, even if we were overlooked with eagle eyes by the teachers, who always ensured everyone behaved correctly.

As my circle of friends increased and became more diverse through contacts I had made since I started work, I decided to begin taking dancing lessons. A group of us enrolled at the Palais-de-Dance, situated in Temple Street, Wolverhampton. These lessons were held on Saturday afternoon from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. and they attracted pupils from all round the Black Country area.

This new interest began in 1943 and I have fond recollections of us all excitedly meeting on every Saturday lunchtime at the Wolverhampton bus stop which in the forties stood directly opposite the old Odeon Cinema, Bilston. It may seem incredible but for any girl from Bilston, Darlaston, Willenhall, Wednesbury or other similar small communities to come alone to a large town like Wolverhampton for dancing tuition, in 1943, amounted to quite an adventure.

One particular new friend named Ruth was much more "worldly wise" than most of us. She knew her way around - well she was 16 - whereas I had no idea how to reach Temple Street. Walking from the bus stop at the Victoria Hotel, Lichfield Street and into the centre of Wolverhampton was, for me, like entering another world. There were numerous uniformed men. RAF Cosford was only a few miles away and this, together with massive crowds of people who were busy shopping and others making for one of the town's two live theatre matinees and numerous cinemas, was, to someone like myself who had seen precious little of the larger world outside of Bilston, all impressively exciting.

Anyhow we continued to attend lessons throughout the winter of 1943. At the same time I still went along regularly to my old Holy Trinity School dance night. In addition I had started to patronise similar dances at Vicarage School in Queen Street. Many of the boys who went there were active members of the town's ATC Training Corps. The school building also served as their headquarters in the mid-forties.

This is me in 1946

This is me in 1946 |

That was how my social life was unfolding until April 1944, when fate undoubtedly took a hand. It was Easter Saturday and two of my friends had decided to go out for the day. This left me at a loose end as I had no one to go to the usual Town Hall municipal dance. My mum suggested I should go down and check whether either of my friends, Joan and Betty, had returned from their visit. I did as she suggested, but disappointingly neither had done so. Seeing my look of disappointment after I went back home, she put forward the idea that I should go on my own, as I would most certainly meet one or the other of my friends there. I decided to take her advice and go anyway. Looking back I remember my heart was thumping and I almost turned round but I strove forward and paid my 2 shillings (10 pence) entrance fee, then quickly bolted up the stairs to the ladies� changing rooms. As usual the place was packed with people busily attending to each other's hair, swapping lipsticks and, at the same time, chatting merrily away about a multitude of things. |

I felt completely isolated and uneasy but, having got that far, I

hung up my coat, changed into my dancing shoes, walked down the steps,

opened the door into the dance hall and frantically searched the floor

to locate someone I knew. Thankfully my eyes alighted on an old school

friend. She was equally pleased to see me and I immediately occupied a

vacant seat alongside hers and was soon in earnest conversation,

oblivious to everyone else around me and grateful to have overcome the

embarrassment of being at a Saturday night dance all alone.

In the forties we lived at 13b Tame Street, a two bedroom property

with just one downstairs room that was both a kitchen and living area.

It was situated in a party yard that also contained two other family

houses. Alongside next door, 13a, there was an entry that led into Free

Street. It must surely have been one of the shortest in the whole of

Bilston. Up until the late thirties it contained four small family

houses but by the early forties these had been demolished. The only

other significant buildings left were a tiny moulding establishments,

known locally as the black sand factory. The name derived from the fact

that there was a huge, permanent bank of nasty smelling black sand

alongside the premises, which was used everyday in its various

production processes. Apart from that the only other premises in that

street formed part of the outside wall of Holy Trinity Infants�

School, in the minute playground and toilet area.

But it was a certain factory situated in the street adjacent that had

a special significance for me in 1943/1944, in particular the Steel

Stove and Truck Company Ltd, based in Hare Street. This was all because

a young man worked there as a welder and, as fate would decree, he would

figure very prominently in the later events of that eventful 1944 Easter

Saturday evening municipal dance.

| Apparently his name was Les Wilcox and for some

weeks past I had noticed that he used the entry alongside our

neighbour's house as a short cut at dinner times in order to

visit the British Restaurant in Tame Street.

My mother continually complained about workmen from the local factories walking through our yards at lunchtime, especially when it was wash day and the weeks washing was strung out across it. She would instruct me to close the entry when I arrived home for my own lunch hour. This I would do, only letting this handsome young gentleman through, at the same time warning him to duck under Mother's precious washing without spoiling anything with his always dirty overalls! On the evening of my daring lone attendance at that fatal dance, as I gratefully sat in the company of the other girls I had attached myself to, my fears about being alone where quickly forgotten. |

Les in 1946

Les in 1946 |

As the evening rolled on I became oblivious to the time, and suddenly my enjoyment was completed because, as I stood up to dance with one of the girls at my table, momentarily glancing across the room I saw my lunchtime friend walking towards me. Before I had time to say "Hello", he asked if he could please have the next dance. That night of 1944 was one of sheer fright, and after over 52 years, there has been no one else for either of us.Our first official date was to be a visit to the Odeon Cinema. I recall that, as was mostly the case throughout the war years, we had to wait in a long queue before gaining admission. Nevertheless after playing a 2/3 p (21 p) each for access to the circle (posh seats) suddenly Les announced "My Mum and Dad are in here somewhere". "Well", I thought to myself, "I'm on show on my first date!"

However it was to be at his 21st birthday treat, a visit to the Theatre Royal, on Mount Pleasant, Bilston, that I first met my future in laws. I was there only because Ruth, one of my Palace de Dance dancing lesson companions worked at the theatre as an usherette. She had kindly provided me with a complimentary ticket for that evening's show and I was already seated with Les and his parents. In the interval he came over and gave me a box of chocolates. I was formally introduced to his mother and father after the show. That essential protocol was the normal pattern of all courtships during the Forties and Fifties, such formalities had all but disappeared by the early Sixties.

|

From then on Saturday night was always a regular

dance date, although very often we only just managed to squeeze

in. The municipal weekly dance was so popular it was touch and go

whether or not we gained entrance.

The authorities employed a policy of issuing pass outs between

9 pm and 10 pm to enable patrons out for a drink at one of the

nearby public houses, because in the forties the town hall was not

licenced for the sale of alcoholic drinks.

There must be thousands of Black Country senior citizens who remember going through the strict procedure required to obtain a pass out. Everyone had to have an ink stained imprint stamped on the back of the hand by the doorman. It's not difficult to imagine the mad scramble to get stamped, race across the road and grab a quick drink. Everyone had to be back by 10 pm and only allowed in after the doorman had checked the identity mark on their hands. |

As our courtship progressed a fixed weekly pattern was established. This became necessary because I was only allowed to go out on Monday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday evenings and furthermore, during mid-week, my mother imposed a 10 p.m deadline. Normally it would be a visit to the cinema on Monday, with an agreement that I could come home a little after the usual 10 pm limit. On Wednesdays we would go for a long walk, mostly along the canal path into Darlaston, or sometimes down Mount Pleasant, past the fever Hospital, on to the golf links, around the pool opposite the Grapes pub, then up through Bunkers Hill, down into Trinity Road, alongside the Brooke Bond tea vehicle garage, over the open patch of waste ground leading into Bissell street, up Tame Street, finally arriving home tired but always happy.On Friday it would be either the cinema or theatre. As for Saturdays, the first priority in the morning was attending to a long list of household chores stipulated by my mother. Then came the shopping duties, a mixture of groceries to be collected from Briscoe's shop in Church Street, bread and various other confectionery from Chattin's Bakery, meat from Riley's the butchers and vegetables purchased at Billingsley's or Berryman's greengrocers, all situated in Oxford Street.

With all the domestic jobs done and the shopping completed, during the autumn and winter months I would then rush to meet Les at the bus stop situated outside the Queen's head public house in Wellington Road, directly opposite the clinic. There was always a long queue waiting for a bus to Wolverhampton - it was never any different whenever the Wolves were playing at home. In those days only a handful of working class people owned a car or motor bike; consequently everyone either walked to the match or stood in queues waiting for a bus. I recall that the single fare from the clinic to the Victoria Hotel was twopence ha'penny. Immediately the bus reached Wolverhampton practically every passenger would alight and make a dash up Lichfield Street and past the open air market to the Molineux football ground.

Quite often we would go straight back home after the

match, change, have a little tea, then off to Bilston railway station to

catch a train to Snow Hill Station. From there we hopped aboard a bus to

Perry Barr for the speedway meeting. Then back on the tram, hopefully to

arrive at Bilston town hall, where we stayed until 9.50 pm, when I would

run down Oxford Street to ensure I kept mother's special Saturday night

concessionary curfew time.T his hectic routine just had to change if we were ever to

save enough money to get married. Employment was never a problem like it

is in today's society. Vacancies were so common that, in the early post

war period, it was simply a question of shopping around; and, if you heard

of a job paying higher wages than your current employment, you handed in

your notice and moved to the better paid one.

The other major difference between the nineties and

forties was, of course, standard working conditions in factories, shops,

and indeed offices. In every instance the general working environments

compared with today were usually appalling. But in those days you learned

to disregard the poor conditions and took the view that the extra wages

were the most important consideration.

Everyone tended to move around and take whatever employment offered the highest remuneration, especially young couples trying to save. For instance over a five year period I had six completely different jobs: shop assistant, senior usherette, wages clerk, time office clerk, booking clerk, and finally factory assembly work, making airplane valves. Each one was financially more rewarding but we still need to increase our joint weekly savings efforts.We decided to restrict our cinema visits to one per week and also to cut out completely all football and speedway. We continued to go dancing but curtailed that to one night only and no holidays - at least no visiting the seaside. Consequently any day trips organised by our works social clubs were eagerly awaited as a rare treat. We did far more walking. My father presented me with a birthday cycle that became my pride and joy. Les had his own which enabled us to extend our leisure pursuits to cycling to Pool Hall, at Dimingsdale, where there was an opportunity for Les to enjoy his love of fishing. While he did so I would sit on the bank alongside, embroidering pillow cases, tablecloths, tray cloths or anything to build up a list of bottom drawer possessions, a procedure and practice adopted by almost all courting couples at that time.

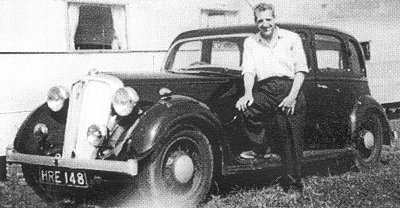

Years later we got a car. This is Les and the car, on holiday in 1955.

Even after almost three years of saving and cutting back on weekly expenditure for cinemas and dancing, we had still not managed to save enough for an engagement ring. Unknown to me Les deliberately sold his treasured fishing tackle for£20, a small fortune in the forties. He used the money to buy an engagement ring. After consideration the choice rested between one costing £19 and another at £12 10s (£12 50p). In the end I chose the latter one, so we had enough money left for a meal out plus a night at the pictures. It was to be many years before I learned of the personal sacrifice Les had made to make that memorable day possible.Our parents jointly organised a lovely celebration party at the Civic restaurant, Tame Street. Everyone brought along gifts suitable for the "bottom drawer", which was the accepted practice for such occasions. Those gifts of sheets, tablecloth, etc, were invaluable, particularly as they were only available with clothing coupons.It was a further two and a half years later before we finally married. It was virtually impossible for ordinary working class couples to save enough from the average wage levels of that period to even think about buying a house. Council property was almost non-existent for married people with children, let alone anyone simply contemplating marriage. This left only two possible options for the vast majority of engaged couples: renting rooms or sharing with one of the in-laws on a temporary basis.

|

Our wedding at Holy Trinity Church, Bilston, 1948 |  |

A wedding day photo |

When we did at last marry in 1948, I remember visiting the local housing office to be abruptly told we qualified for just two housing points! A hopeless situation. As there was no spare room at either parent's home, we really had a major problem. Fortunately my elder sister Jossie and her husband Joe possessed a spare bedroom in a rented house they tenanted in Hadley Road, so we thankfully moved in with them.Both our parents put together to buy us a bedroom suite. Much time and many visits were made to the local furniture store to choose this bedroom suite. Most within our price range were confined to the standard utility line of the mid-forties. I remember so clearly that the one we finally settled for cost just short of £100.00. It proved to be a wise selection - that same suite lasted us 34 years! When we moved into a bungalow we rather reluctantly gave it to charity.

After our marriage, we carried on dancing. My love of ballroom dancing has continued throughout my life