|

A History of Bilston6. Industrial Growth |

|

The proximity of coal to the surface in Bilston enabled the "open cast" system of mining to be practised from the infancy of the industry until the late nineteenth century. Thus rich deposits of iron and coal, easily and cheaply worked, together with the limestone from the neighbouring hills, dictated the rise of Bilston's fortunes as a centre of the iron and coal trade in the Black Country. Another important factor in maintaining the location of an industry that rapidly gathered impetus was Bilston's proximity to the sandstone water-bearing area south-west of Wolverhampton.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century the manufacture of iron had migrated from the Bilston area through the exhaustion of charcoal supplies, and had settled in districts along the River Severn where extensive woodland was still able to meet the charcoal demands of the iron furnaces. It was to these districts, during the period of exile of the iron industry, that the Bilston smith had been forced to turn for his supply of finished iron.

|

The Bilston district has been associated with many of the great names and discoveries of the Industrial Revolution. The finest plant for de-watering mines was installed on the coalfield by Savery in the early part of the seventeenth century Newcomen's engine was erected in 1712 at a coalpit near Bilston. |

In 1756 John Wilkinson settled in Bradley and in 1767 established his blast furnace for the manufacture of pig-iron. It was Wilkinson who first made Boulton and Watt's steam engines, and in 1775 installed one at his Bradley works and in the process doubled his iron output. It was he too, who in 1784, first applied, and then improved, Henry Cort's invention of the puddling furnace and rolling mill. His inventions and adaptations, so quickly applied to industrial production, made the town the most important centre on the South Staffordshire Coalfield.

| In 1790, of the 21 blast furnaces in the Black Country, 15 were at work

in Bilston. Pig and wrought iron were both produced in ever increasing

quantity and with the expansion of the basic trades the town became an

important manufactory of the subsidiary trades of Japanning, sheet metal,

galvanising, tin plate and wide range of domestic hardware.

Unlike Birmingham, which relied upon the Black Countryfor its raw materials and owed its prosperity to the more skilled and varied branches of the metal trade, particularly engineering, the Bilston district, apart from the production of basic materials, was more concerned with the less skilled processes of which the manufacture of hardware and domestic utensils were typical |

|

|

The construction of the canal from Birmingham to Aldersley, near Wolverhampton in 1767, was the work of James Brindley. Upon it Wilkinson launched the first iron boat. The canal forms an exaggerated loop south of Bilston most probably to take in the area covered by the coal and iron works at Bradley. After its construction the price of coal at Birmingham dropped from 13s to 8s4d a ton, but by 1820 the canal proved itself unable to cope with the traffic it attracted, so that Telford was called in to extend and improve it. |

Along the canal new factories and mines sprang up. Bilston grew rapidly. The population increased from 6,914 in 1801 to 12,003 in 1821. By 1841 the population had reached 20,181 but after 1850 increases halted. The heyday of Bilston had passed and the town declined in prosperity after 1860.

The output of the South Staffordshire Coalfield was largely absorbed locally and by the Birmingham industries, but nevertheless its canal system, even improved, was not adequate to meet its industrial needs.

| In 1837 the Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool Railway was constructed and passed through Bilston. The Great Western Railway Station at Bilston (Bilston Central) was reputedly the work of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the great railway engineer. The railways which cut across the town, accentuating its linear formation, were a decisive factor in extending the markets for the products of the town, and as the sources of raw materials became increasingly exhausted, enabled supplies of coking coal to be brought into the town for the mills and furnaces. |

|

By this means the industry, which had come to rely after 1860, to an alarming extent, upon the local supplies of cinder tap, which, prior to 1840, had scarcely been touched, was able to keep its production going.

Coal and iron were so easily extracted in the Bilston area that the coalfield was exploited to the full, without regard to the economic working of the riches upon which the town's economy relied.

|

In addition to the "open-cast" system the "Bell" or

"Beehive" method of working was extensively practised. This type

of shaft was sunk through the overburden to the coal and then widened or

" bellied out" at the bottom. On subsidence threatening, the

shaft was abandoned and another sunk nearby. In times of excited trade the

small man could sink a shaft, work in it, and, in time of depression,

abandon it just as easily.

By this means the natural drainage of the underground workings was rapidly destroyed and by 1860, signs of the exhaustion of the coalfield were too clearly apparent |

In 1873 the South Staffordshire Mines Drainage Act was passed enabling a Commission to investigate the flooding and to arrange for the pumping of the area. Between 1873 and 1914 no fewer than seven Acts of Parliament dealing with the problem were passed.

Bilston suffered particularly. Out of 423 collieries in the coalfield (South of the Bentley fault) in 1860, 64 were in Bilston and 26 on the Bilston side of Wolverhampton. The magnitude of the problem, so far as Bilston was concerned, can therefore be gauged: about 10% of the total population were colliers. In 1827 Bilston's annual production of coal amounted to 316,740 tons ; in 1874- 640,926 tons; in 1880 - 204,531 tons and by 1920 production had ceased. In these figures too can be traced the fall of the iron industry

The scale of organisation, which Wilkinson and the Bilston iron founders had established, dictated the pattern of industrial Bilston and persisted throughout the nineteenth century, substantially unaltered.

It was an age of integrated concerns, the great iron masters not only owned the furnaces and foundries, but the collieries too. The machinery of coal mining remained to the end comparatively simple and inexpensive but the equipment of furnaces and foundries required capital outlay.

In this respect the basic industry contrasted strikingly with the trades and processes such as Japanning, metal box, and domestic hardware, whose organisation developed into shape or system. In the eighteenth century, the lighter metal working processes had been carried on in the home. As the Industrial Revolution progressed the home became enlarged, in many cases into work-shops. In this respect the South Staffordshire area offers a contrast to the large factory organisation of the textile industry of Lancashire during the same period.

"There are few manufactories of large size, the work being carried on in small workshops, usually at the back of houses, so that the places where children and great bodies of operatives are employed are completely out of sight in the narrow courts, unpaved yards and blind alleys.

In the smaller dirtier streets, in which the poorest lived there were narrow passages at intervals of every eight or ten houses, and sometimes every third and fourth house; these are under three yards wide about nine feet high and they form the general gutter. Having made your way through the passage you find yourself in a space varying in size with the number of houses, hutches, or hovels it contains, all proportionally crowded. Out of this space other narrow passages led to similar hovels, the workshops and houses being mostly built in a little elevation sloping towards the passage. The great majority of yards contain two to four houses, one or two of which are workshops or have room in them for a workshop.

In process of time, as the inhabitants increased, small rooms were raised over the workshops and hovels were also built whenever space could be found and tenanted first perhaps as workshops and then by families also.

By these means the increasing population were lodged from year to year while the circumference of the town remained the same for a long time, owing to the difficulties of obtaining land to build upon ."

In all branches of Bilston industry, in the basic as well as the subsidiary processes, the overhand system had taken root. In the coalfield the overhand was known as a "butty". He was an independent contractor, who contracted with the coal owner to extract a given amount of coal for an agreed price; and he then contracted with colliers to do the actual work at a fixed wage. One of the points of grievance considered by the midland Mining Commission in 1843 was that "the butties keep beer shops and public houses themselves, or have an interest in them, and consequently devise means for inducing men to spend their wages which they ought to carry home to their families, in drink." Such abuses of the system were a constant source of social discontent throughout the century but persisted right up to the end of the period in which the coalfield was a centre of production.

It would appear that the case was proved; in 1842 there were eighty two taverns and seventy seven beer shops in Bilston.

The extensive exploitation of every available plot of land for coal and iron working and the social consequences of its industries produced a town thus described in the Midland Mining Commission of 1843:

"In some directions one may travel for miles and never be out of sight of two storied houses interspersed with blazing furnaces, heaps of burning coal in process of coking, piles of ironstone calcining forges, pit banks and engine chimneys besides intersecting canals crossing each other at various levels, and the small remaining patches of surface soil are occupied by irregular fields of grass and corn intermingled with heaps of refuse of mines, or from the slag of blast furnaces.

"Sometimes the road passes between mounds of refuse from the pits, like a causeway on either side which have subsided by the excavation of the minerals beneath. These circumstances in the state of the surface and the substrata united to clouds of smoke from the furnaces, coke heaths and heaps of calcined ironstone, which drift across the country according to the direction of the wind, have effectually excluded from it all classes except those where daily bread depends upon their residence within the district"

It is hardly surprising that the town suffered cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1849 which reached plague proportions.

Bilston�s situation in a rich coal, iron, limestone and fireclay area, and the excellent communication systmes which developed, ensured its prosperity during the malleable iron period. But these favourable factors tended to perpetuate a way of life associated with heavy industry, to the exclusion of the variety and diversity of industry which have contributed to the continuing expansion and prosperity of towns like Birmingham and Wolverhampton.

The decline of the iron trade in Bilston was due not only to the exhaustion of the area of supply but to the establishment of new centres of iron production at places like Middlesborough and on the coast and, in the latter part of the nineteenth century to the foreign competition.

The invention of basic steel by Bessemer and the steel processes invented by Siemens assured the substitution of steel for iron in a multitude of uses and introduced a new orientation of industrial location. In 1883 one of the first plants in the country for the production of mild steel was set up in Bilston. Steel in such circumstances was a factor in bringing new industries to the town but it had the effect of absorbing the traditional skill. Many of the Bilston firms engaged in the production of hardware adjusted their processes to the new demands, but it was not until after 1919 that any considerable movement towards new industries took place in Bilston.

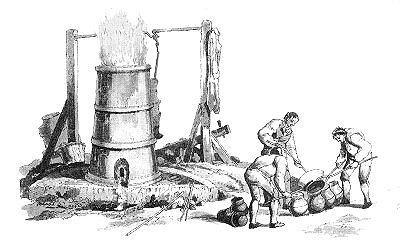

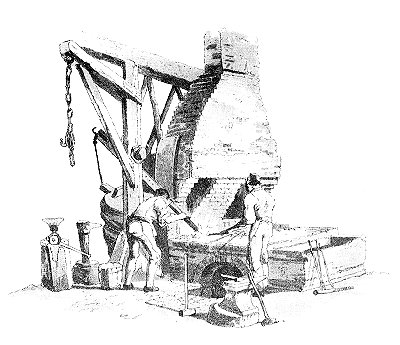

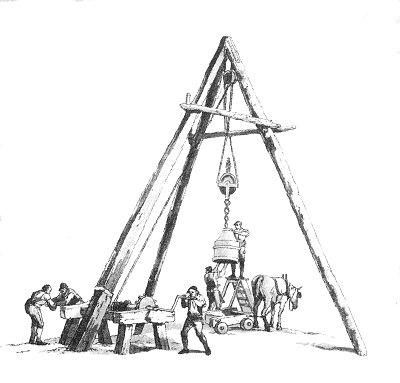

Note: the drawings on this page and the previous page are taken from Pyne's Microcosm, published in 1808.