|

Bradley & Co. Ltd (Beldray) Mount Pleasant, Bilston A short account by former employee George Philpott |

|

|

The company's premises at Mount Pleasant, Bilston,

are locally listed as a good example of 1930s architecture. They are now occupied by the Wolverhampton City Council social services and the company's works lie behind them |

|

The company's logo can still be seen above the door of their old offices |

Starting out

Hector had been wounded or gassed and we seldom saw him at the works. In fact a few years after I joined the company he died and I remember that one of the works vans was filled with flowers on the day of his funeral.

Herman liked fast cars. I think that in his youth he had raced at Brooklands. He travelled to the works from his home on the Thames in a French car, a Darracq, and although he had a chauffeur he used to take the wheel himself when they hit the open road (there were no motorways then).

Conditions of employment were rather different then to those of today. This is not any criticism of Bradley's - it was common practice among employers. They would take on school leavers, such as myself, and when a few years later they had to start paying them adult wages, they would sack them and take on other juveniles. I had been at work there for several weeks before I found out that I had been given the job from which a very good friend had been dismissed (but there were no recriminations).

My first job was to help to make coal scuttles. They were called "Waterloos" because they were shaped like the hats which soldiers wore at the Battle of Waterloo. After about twelve months I went into the tool room as an apprentice tool maker. This meant a drop in wages but it ensured that I would still have a job after I reached the age of 18 and that I would have a trade to my name. The tool room foreman was a man of most uncertain temperament and, apparently because he frequently referred to peoples as "proper Job's comforters", he was known as Joey. He called everyone "Chile", in much the same way that men today used the terms "mate" and "pal". I do remember, however, one pearl of wisdom that he imparted to me: "Remember this, Chile, the man who never made a mistake, never made anything".

The company had an excellent reputation as makers of high quality domestic wares, and the product range included dustbins, buckets, household shovels, kettles of all sizes, watering cans and a host of other items, including frying pans by the thousands. Most of the products were galvanised, though some were tinned and others, such as kettles and coalscuttles, were black enamelled. Some of these items we made then have now passed into history such as the small hand bowl, with a wooden handle about 6" long, with which the housewife would ladle the water out of the washing tub when washing was done. Another was the mortar bowl, a large steel receptacle shaped like a pudding basin, which had been flattened somewhat, and about 24" in diameter. I never saw them in use but I always understood that ladies in Africa carried them around on their heads with goods and merchandise in them. Yet another was the egg bucket, a specially designed bucket, the purpose of which was to preserve eggs before the days of the fridge. A substance called isinglass (which Bradley's did not provide) was added to keep the eggs in good shape.

|

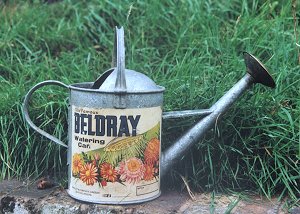

This is me holding a watering can, which I can still remember

making the tools for. |

| The watering can, from Reg Aston's collection, is dated before 1950. The body is galvanised iron and the rose is brass. With its original label it is now a rare survivor. |

| This display at the Made in Bilston Exhibition, 2002, shows many pieces of Beldray brass and copperware and some chrome plated ware too |  |

This is another of

Beldray's many products: the Rapid Vacuum Ice

Cream Freezer. It was like a huge vacuum

flask. You packed ice and salt in the bottom,

round the flask, then poured your ice cream mixture into

the flask at the top. Then you left it until it

froze. The instruction book which came with it explains that ice cream is particularly good for you because it contains so many calories! It even provided a list of other foods, including chocolate, which had fewer calories and which were, therefore, not so beneficial. I think this device was made in the 1920s or 30s. |

|

|

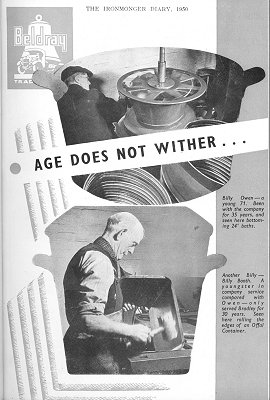

Left an early Beldray Advert | Right: An advert from 1950, showing, at the top, Billy Owens, then aged 71; and, at the bottom, Billy Booth. They both symbolise the traditional craftsmanship of the factory. |

|

Thousands upon thousands of paint cans were made, some bearing proprietary names such as "Walpamur". One shop made oval tin baths and in the tool room was a machine which I believe was most unusual. It was a lathe made by Maud & Turner. It machined no circular but elliptical shapes on which tools were machined to produce the bottoms of the oval baths and oval frying pans. The rise and fall of the revolutions of the lathe head were achieved by a series of cams and slides. Needless to say it did not revolve very fast. But there were more arrows in the Beldray quiver than kitchen utensils. They made a charming selection of ornamental vases, rose bowls, cake stands and the like, from sheet copper and brass. These were made in what was virtually a separate factory, though within the Mount Pleasant premises. It was known to one and all as the "Copper Side". The manager of the "Copper Side" was Mr George Freeman.

Freeman Place, off Bunkers Hill was named after him, since he bought one of the first houses in that culde-sac, (though others may say that it was named after his wife, Mrs Hattie Holland, a JP and local councillor who represented the New Town Ward on the Bilston Urban District Council).

Similarly Holland Road was named after Mr Albert Holland, the foreman/manager of one of the large machine shops. On the copper side I remember there was a German made machine which used to roll the patterns into the brass and copper sheet used for vases and the like. I think it was installed just before World War 2. It was operated by Herbert Martin. The company was making this brass and copperware at least up until the time I left. The manager then was George Freeman, the foreman was Rubin Timmins and the forewoman was his wife, Floss Timmins. The shop foreman over the spinning of bowls was George Lee.

|

The Despatch Department was presided over by Mr

Walter Williams and included in his staff was his elder son,

also named Walter. He had a younger son, Bert, who I believe

worked at Bradley's for a short while before moving on to fresh

fields, namely those at Wolves, Molineux, Wembley and others

further distant.

An old chap who appeared in many of Bradley's adverts was Billy Owen. One of these adverts is shown on the right. I knew him very well, although he was old enough to be my father. He lived near us, in Beech Road, and we sometimes walked to work together - before I got my first bike! The shop in which we worked was known as Hayward's Shop, for the simple reason that that was the foreman's name. Billy's machine was the only piece of machinery in that shop. Everything else was bench and hand work. In the picture he is rolling together the body and the bottom of an oval bath tub, to make a watertight joint and seal. (You can just make out the shape of the bath through the slots in the plate and spindle which were holding them in place while they revolved). Note that in the advert above Billy Booth's age is not mentioned. I have been shown a letter by a descendant of his, which was sent in response to his daughter writing to ask if Billy Booth could retire. The reason for that was that in those days you were not entitled to a pension but the company might grant you one if you had worked there many years. The letter, sent in December 1953, comes from Hermon Bradley saying "I am surprised to hear he is as old as 76" and that "he has been a very excellent servant to the company in all ways". And "iof he retires he will certainly get a pension and he will also get a lump sum for the number of years he has been here ... and I certainly agree that if it is knocking him up it is certainly time he retired". I suppose that in all factories there were, and still are, certain "characters". I remember one chap who worked in the galvanising shop as a labourer and who, to put it kindly, was not very bright. The men in the shop were very protective to him and woebetides anyone who tried to "take the Mickey". He used to use the Market Tavern pub opposite the Market Hall where some clever people used to amuse themselves and others by lining up a shilling, a sixpence and a penny on the bar, then inviting him to take one. He always took the penny, because, so they thought, he believed it to be the most valuable because it was the largest. Someone asked him why he didn't take the shilling since it was worth so much more. "I know it is" he said, "but if I was to tek one o' them they wouldn't do it again would they? They think I'm saft". Then there was George, the works blacksmith. A man who was very much overweight but who could swing a sledgehammer with the best of them. It was he who told me the story of the blacksmith who was training a new striker and told him. "I shall put the red hot iron on the anvil and when I nod my head, you hit it as hard as you can". |